Hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Symptoms and the

Parasympathetic and Sympathetic Nervous Systems

Stephen Soloway, MD, FACP, FACR; Nicholas L. DePace, MD, FACC; Joe Colombo, PhD, DNM, DHS

SUMMARY

Background

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome/Hypermobility (EDSh) is a connective tissue disorder caused by abnormal collagen, resulting in hyperflexible joints, soft/“leaky” connective tissue, and systemic symptoms. Though non-life-threatening in most forms, EDSh significantly impairs quality of life. A hallmark feature is autonomic dysfunction (AD), particularly Sympathetic Withdrawal (SW), which contributes to orthostatic intolerance, fatigue, diffuse pain, brain fog, and exercise intolerance. Diagnosis remains clinical, using Beighton scoring and the EDSh Society checklist, as no definitive lab or imaging test exists.

Methods

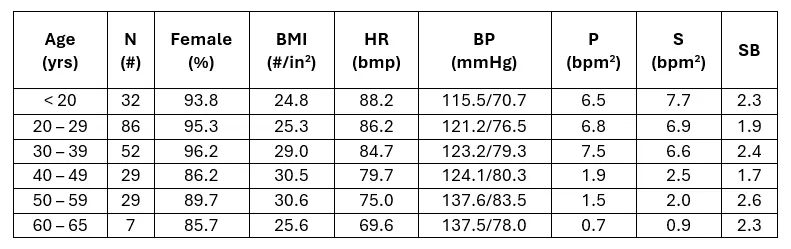

Between Nov 2018 and May 2020, 569 EDSh patients (94.2% female, mean age 30.4 years, range 13–65) were referred to a suburban cardiovascular/autonomic clinic in the northeastern U.S. Patients underwent detailed history, physical exam, and serial Physio PS P&S Monitoring (direct measures: LFa = Sympathetic, RFa = Parasympathetic, SB = sympathovagal balance). Additional testing included vestibular assessment, mast cell bloodwork, small fiber neuropathy evaluation, and cardiology screening. All patients had ≥2 follow-up P&S assessments.

Results

Sympathetic Withdrawal (SW): Detected in 49.4% of the cohort, predominantly younger patients.

Orthostatic Dysfunction: 104 patients exhibited orthostatic hypotension. P&S monitoring identified OH risk more reliably than HRV alone (p = 0.009).

Morbidity/Mortality: Only 14.4% demonstrated advanced AD. No patients <65 years showed late-stage autonomic neuropathy. EDSh does not appear to increase natural mortality risk, but does impair productivity and quality of life.

Symptom profile: Common complaints included diffuse musculoskeletal pain, palpitations, dizziness/fainting, fatigue, brain fog, sleep disturbance, and hypersensitivity to light/sound—consistent with AD manifestations.

Therapeutic response: Targeted treatment (r-Alpha Lipoic Acid plus low-dose vasoactive agents) relieved SW and improved quality of life in >85% of affected patients. Residual cases were linked to overlapping dysautonomias or comorbidities.

Conclusion

EDSh is strongly associated with autonomic dysfunction, particularly SW, which significantly contributes to symptom burden and reduced quality of life. While resting HR, BP, and standard HRV measures appear normal, P&S monitoring reveals underlying dysfunction and guides targeted therapy. Early detection and treatment can restore function and productivity in most patients, despite the absence of curative therapies for EDSh.

Hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Symptoms and the

Parasympathetic and Sympathetic Nervous Systems

Stephen Soloway, MD, FACP, FACR; Nicholas L. DePace, MD, FACC; Joe Colombo, PhD, DNM, DHS

INTRODUCTION

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome/Hypermobility (EDSh) defines a spectrum of connective tissue disorders that are caused by defects in the genetic information that is used in humans to produce collagen. In both, the collagen is long and flexible, rather than short and stiff. This results in loose and “leaky” connective tissue. EDSh may be inherited, usually an autosomal dominant trait; however, acquired cases occur frequently. To date, there is no known cure for EDSh. However, there are a few characteristics that are well known (in no particular order): 1) females tend to be significantly more than symptomatic than males (due to the fact that males tend to be born with greater muscle mass and larger cardiac stroke volumes); 2) in the young, the additional flexibility seems advantageous due to the lack of significant symptoms (due to the fact that the Autonomic Dysfunctions (ADs) are masked by the three stages of growth and development); 3) generally, around the end of development (during early to mid-20s), symptoms begin to present, and generally active and vivacious people become sickly for no apparent reason with poor productivity and, frequently, debilitating qualities of life. [1]

Another primary characteristic of EDSh patients is that they demonstrate some degree of AD (a.k.a., dysautonomia). This may explain the last two characteristics listed above. During development, except for a couple of years around ages 8 and 15 when development slows down, the ANS is very active in development; therefore, AD symptoms are masked and the symptoms that appear are attributed to current factors with largely unknown histories. Once development ends, in the early to mid-twenties, AD symptoms are unmasked and the effects of a persistently overactive ANS presents. In general, AD is the effect of an imbalance between the two autonomic branches: the Parasympathetic and Sympathetic (P&S) nervous systems [1]. Here, we introduce a clinical cohort and some general characteristics of P&S function.

METHODS

From a single, suburban, cardiovascular and AD clinic in the northeastern United States of America (USA), 569 patients (226 female, 94.2%; average age 30.4yrs, range 13 to 65 y/o; average height 64.5 in; and average weight 158.3#) previously diagnosed by Rheumatology with EDSh were referred from November 2018 through May 2020. All patients had a minimum of two follow-up P&S Monitoring tests. This patient cohort included a significant number of patients from across the USA and abroad. Detailed patient histories and physicals were taken as routine, including completing a Beighton Scoring test and the EDSh Diagnostic Checklist from the Ehlers-Danlos Society (www.ehlers-danlos.com). Testing included Vestibular testing; Mast Cell blood work; Small Fiber Neuropathy testing; age- and symptom-specific cardiology testing; and serial P&S Monitoring (Physio PS, Atlanta, GA), which includes HRV measures [2,3]. P&S Monitoring includes LFa as the direct measure of Sympathetic (S) activity, RFa as the direct measure of Parasympathetic (P) activity, and Sympathovagal Balance (SB=S/P, measured at rest as the average of ratios, not the ratio of averages) [4]. These are all quick, in-office tests. All patients had a minimum of two follow-up tests.

DIAGNOSIS

The typical patient presents with diffuse pain, especially in the shoulders, upper back, inter-scapular area, jaw, and hips. The patients oftentimes complain of their joints being quite flexible and oftentimes subluxing, or popping out. It is not unusual for the patients to have their knees, elbows, ankles, wrists, and even jaw pop out, or their cervical spine be hypermobile. Even hyper-flexibility in the lumbar spine may make the patient able to touch the ground with their palms to the ground and knees straight quite easily. Patients typically complain of shortness of breath and palpitations. They do not stand for long periods of time and get dizzy and may have a history of fainting or near-fainting, and oftentimes have to lie down when trying to stand for periods of time. Oftentimes, the patients are extremely tired. They often complain of sleep difficulties, and they cannot get going in the morning. They complain of brain-fog or memory and cognitive difficulties. Bright light or sound may disturb them. These symptoms, not including the joint issues, are all symptoms of dysautonomia, including the possible amplification of pain and Fibromyalgia-like pain also due to dysautonomia.

Many patients state that they were quite athletic and were good dancers or good gymnasts during grade school and high school. They even comment that they believe they are double-jointed. A family history of this is often important in determining whether a person has Hypermobile or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. The skin is oftentimes soft and very hyper-extensible (the skin on the non-dominant forearm stretches more than 2 cm). The skin may also be velvety and mildly hyper-extensible. Patients may have striae on their back, thighs, breast areas, and abdomen, and they may also have a history of recurrent hernias of the abdomen or inguinal area. Interestingly, some patients give a history of pelvic floor abnormalities with rectal or uterine prolapse as children. Some patients may present with arm spans greater than their height spans. However, other entities such as Marfan’s Syndrome should be considered first with this presentation.

The combination of the Beighton score and the EDSh Diagnostic Checklist provides a better diagnostic yield than either alone. Still, a detailed history and physical is important to find systemic features that reflect the syndrome, such as 1) family history, 2) many musculoskeletal complications such as pain in several limbs that has been occurring for more than three months, 3) pain that is widespread, or 4) recurrent (spontaneous) joint dislocations or joint instability without any trauma. In older EDSh patients, including those in their 40s, arthritis and weight-gain due to exercise intolerance often limits mobility, making the detailed history more important.

Other possibilities that may mimic EDSh must also be excluded, such as Lupus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Scleroderma. These other possibilities also have abnormal collagen and connective tissue as does EDSh and can give joint laxity and hypermobility, but have other features, some of which can be life-threatening. Many rheumatologists refer patients whom they have evaluated for connective tissue disease and have excluded these other possibilities. The referrals are then for autonomic dysfunction. Also, the inappropriate label “Fibromyalgia” oftentimes is applied to EDSh.

Unfortunately, there is no blood test, lab test, or imaging modality that confirms a diagnosis; therefore, the diagnosis is completely clinical. What may complicate the issue is there are some patients who present with this syndrome complex de-novo and do not have a family history despite a careful search from the physician and clinician. These are the minority of cases, however, and the exact percentage is not known.

It is not difficult to diagnosis EDSh, but a very detailed history and physical examination is required. A very thorough family history is also required, and this may even involve examining some of the family members. Excluding other entities that present with abnormal collagen composition or other types of hereditary tissue diseases is extremely important and consultation with a skilled rheumatologist and a P&S nervous system expert is often needed. Generic testing may be useful to exclude vascular-type EDS, Marfan’s Syndrome, and other related connective tissue diseases.

RESULTS

While resting P&S balance (SB, see Table) for the cohort is well within normal limits (SB: 0.4 < SB < 3.0, unitless); preferred SB for younger, < 65 y/o, healthier subjects is 1.0 < SB < 3.0; and preferred SB for older subjects, ≥ 65 y/o, and sicker patients is 0.4 < SB < 1.0; the latter is known to be cardio-protective [5] and protective of bodily systems in general. No patients in the age range of the cohort (< 65 y/o) demonstrate late stage autonomic neuropathy. In other words, EDSh does not affect natural mortality risk. Only 25 patients total (14.4%) demonstrated advanced AD. In other words, EDSh also does not affect natural morbidity risk beyond what is common from the AD directly associated with EDSh. Overall, patients appear normal at rest. Perhaps their BPs are elevated, arguably due to the pain, but the rest of their resting results as taken from a typical office visit are well within normal limits. We find that the elevated parameters are beta-Sympathetically medicated an tend to be compensating for other co-morbid ADs.

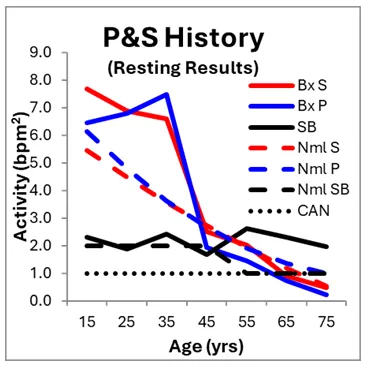

Here, we differentiate autonomic from P&S testing because most autonomic tests (e.g., tilt-table testing) test only total autonomic function, forcing assumption and approximation to theorize specific P&S dysfunction, whereas P&S Monitoring specifies P from S dysfunction, objectively and quantitatively, and enables serial testing for trending and follow-up. In the case of this cohort, the resting autonomic test results (LF, HF, and LF/HF ratio) are well within normal limits. The P&S results are within normal limits, but rather elevated in the 20s and 30s as compared to age-matched Normals (see Figure, left), and their balance (SB) is within normal limits throughout.

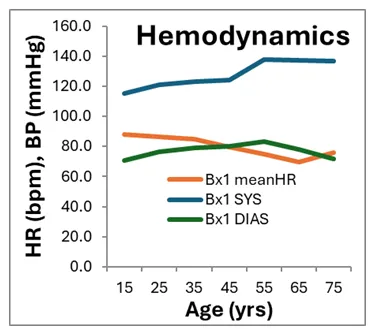

With specific P&S measures, a history of the P&S responses to EDSh is possible and helps to frame an understanding of the effects of the disorder. First, consider more common measures of the ANS. EDSh patients’ resting HRs (bpm) and BPs (mmHg, Systolic or SYS, and Diastolic or DIAS) are displayed in Figure, right, plotted against age (in years). On average, both HR and BP measures are within normal limits throughout the history of the disease. This contributes to the perceived, apparent normalcy of these patients. Many of these patients are often not believed by their physicians because all of the (resting) office measures are within normal limits.

Unfortunately, EDSh is one of the diseases or disorders (like Fatigue or Anxiety) that do not present as abnormal at rest. Rather, the associated dysautonomias are manifested while active (which is the usual condition of the ANS; it rarely rests, as one branch or the other is always active). Similar to the Hemodynamic measures, the HRV measures are also within normal limits (data not shown, see [1]). These are some of the reasons why patients are marginalized, dismissed or referred to psychiatric evaluation.

EDSh patients’ resting P&S data are displayed in the Figure, left, above. For comparison, the P&S history of 302 normal, age-matched subjects (Nml, 55.6% Female) are included. Normal is defined as not under physician care and not on any prescription medications. On average, younger EDSh patients’ P&S activity is high-normal compared with Normals. Eventually, the EDSh patients’ resting P&S activity normalizes, as compared with the Normal subjects’ resting P&S activity. Note, however, the Normals’ resting P-activity is higher or virtually equal to their resting S-activity; whereas, the EDSh patients’ resting P-activity is lower than their resting S-activity, indicating a higher morbidity risk, a complimentary reduced quality of life, and productivity.

Half of all EDSh patients demonstrating POTS also demonstrated co-morbid Vasovagal Syncope; the latter being the cause of fainting or near-fainting. One cannot faint from POTS unless heavily beta-blocked . The Tachycardia prevents the fainting an is a compensatory mechanism [6]. Of the EDSh population, 20.2% present with HTN. Often HTN is a compensatory mechanism for stand or postural change abnormalities. In these cases, it seems that the higher resting BP helps to prevent too low a cerebral perfusion pressure when the patient’s BP drops upon assuming an upright posture [7].

DISCUSSION

From the P&S History figure, younger EDSh patients’ P&S activity is high-normal possibly due to their heightened immune state (including more active histamine and inflammatory activity) and their body’s attempt to heal the “leaky” connective tissue. In EDSh cases, S-activity is typically inflated by the elevated P-activity and the additional S-activity drives the additional inflammation, amplifies pain responses. EDSh is believed to not be life-threatening, except for one form of EDS (the vascular form). However, based on these sample populations, EDSh may perhaps reduce length of life an average of 10 years, given that they cross the Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy (CAN, defined as P < 0.1 bpm2) threshold up to 10 years earlier than Normals. Again, P-activity is protective. The more reduced P-activity in the EDSh patients may be the cause of the reduced life span. It may indicate an immune system that has fatigued earlier or it may be responsible for earlier onset cardiovascular disease-risk (heat attack, stroke, heart failure, etc.). However, by detecting P&S dysfunction earlier and maintaining proper P&S balance (SB) morbidity risk is normalized to that of normals [4].

Many patients present with prior diagnoses of depression and anxiety or psychiatric illness attributed to them, but they know they have something real and abnormal that is not purely psychiatric. The patients hurt all over and have diffuse pain, which keeps them from functioning properly. They are often diagnosed as “Fibromyalgia” or “Chronic Pain Syndrome.” Many cannot perform any gainful employment. Certainly, they become anxious and depressed because of their non-functional status. AD features, such as exercise intolerance, orthostatic intolerance (where one cannot stand up without getting brain fog or dizzy), and chronic or persistent fatigue are almost universally present in these patients. There is a high percentage of females with this problem, but we do also see males in addition, since it is believed that if a person has this disorder, they can transmit it genetically to one or two of their children (autosomal dominant transmission).

It is well known that the P&S is, generally, very active during development. This level of activity, masking any effects of excessive P&S activity, may explain why symptoms do not present until after development. It has been postulated that “leaky” connective tissue permitting foreign items to leak in causes a persistently heightened immune response and greater oxidative stress causing fatigue and more significantly damaging nerves, including brain cells. This in turn leads to a persistent state of Parasympathetic Excess (PE). PE amplifies (beta) Sympathetic responses including pain, anxiety, HR, BP, inflammation, histaminergic responses from overactive Mast Cells, etc. Unfortunately, given that there is no cure for EDSh, these patients tend to be on treatment or therapy for life. The therapy helps to maintain P&S balance (both at rest and during activity, and thereby maintaining quality of life and productivity. Again, all ADs are treatable.

A final thought for now. Since the human body will assimilate foreign, ingested, collagen (i.e., from bones, shellfish shells, and other animal connective tissue), perhaps this is a basis for some relief of EDSh. The (normal) animal collagen may help to “plug the leaks” caused by the abnormal native collagen. Many patients empirically find relief of symptoms with intake of collagen products.

CONCLUSIONS

As mentioned before, there is no genetic testing or lab testing that is diagnostic of EDSh. That is not to say that we will not in the future hone down on a specific gene loci or other biomarkers that may be supportive of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. However, to date, there are none. We use a scoring system developed by the EDS Society. For now, it is possible to re-establish P&S balance and thereby help to restore an improved quality of life that permits a productive lifestyle, with less pain and better sleep [1,8]. This is just the beginning of a research effort that must include many more patients from many more sources as EDSh awareness continues to grow.

REFERENCES

1. DePace NL, Santos, L; Goldis M, Acosta CR, Munoz, R; Ahmad, G; Verma, A; DePace Jr. NL, Kaczmarski K, Colombo J. Hypermobility/Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and the Parasympathetic and Sympathetic Nervous Systems. J Individ Med Ther. 2022, 1(1).

2. Malik, M. The Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability, standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. 1996; 93:1043-1065.

3. Malik, M. and the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability, standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. European Heart Journal. 1996, 17: 354-381.

4. Colombo J, Arora RR, DePace NL, Vinik AI. Clinical Autonomic Dysfunction: Measurement, Indications, Therapies, and Outcomes. Springer Science + Business Media, New York, NY, 2014.

5. Umetani K, Singer DH, McCraty R, and Atkinson M. Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: Relations to age and gender over nine decades. JACC. 1998; 31(3), 593 – 601.

6. DePace NL, Acosta CR, DePace Jr. NL, Kaczmarski K, Goldis M, Santos, L; Munoz, R; Ahmad, G; Verma, A; Colombo J. Hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Symptoms are Explained by Abnormal Sympathetic Responses to Head-Up Postural Change. J Individ Med Ther. 2022, 1(1).

7. Arora RR, Bulgarelli RJ, Ghosh-Dastidar S, Colombo J. Autonomic mechanisms and therapeutic implications of postural diabetic cardiovascular abnormalities. J Diabetes Science and Technology. 2008; 2(4): 568-71.

8. DePace NL, Colombo J. Autonomic and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Clinical Diseases: Diagnostic, Prevention, and Therapy. Springer Science + Business Media, New York, NY, 2019.

This syndrome affects just under 200,000 people each year.

People with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) often experience issues with their autonomic nervous system, which controls automatic body functions like heart rate and digestion.

This condition, called dysautonomia, happens when there is an imbalance between two parts of the nervous system: the Parasympathetic (which helps the body relax) and the Sympathetic (which helps the body respond to stress).

While scientists are still exploring what causes EDS, research shows that the nervous system dysfunction linked to the disorder can be identified, diagnosed, and treated. This research is just the beginning...

More studies with larger groups of patients from different backgrounds are needed to better understand and manage EDS as awareness continues to grow.

A defining feature of EDS is autonomic dysfunction,

ALL FORMS OF DYSAUTONOMIA ARE TREATABLE & CURABLE!

Autonomic dysfunction, also known as dysautonomia. Dysautonomia is generally caused by an imbalance between the two branches of the Autonomic Nervous System: the Parasympathetic (rest & digest) and the Sympathetic (fight or flight) nervous systems.

This may help explain the delayed onset of symptoms. During childhood and adolescence, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) is highly active in supporting development, which may mask dysautonomia symptoms.

However, as development slows in the late teens or early twenties, dysautonomia symptoms become more apparent, often resulting in persistent autonomic nervous system overactivity.

What to Know About Identifying EDS

Several key characteristics have been identified:

1) It affects females significantly more than males;

2) In childhood, the increased flexibility may seem beneficial due to a lack of severe symptoms; and

3) Symptoms often emerge in late adolescence or early adulthood, causing previously active individuals to experience a decline in health and quality of life.

Patients with EDS often experience widespread pain, particularly in the shoulders, upper back, between the shoulder blades, jaw, and hips. Many report joint hypermobility, with frequent subluxations (partial dislocations) or joints popping out of place, affecting the knees, elbows, ankles, wrists, jaw, and even the cervical spine.

Hyper-flexibility in the lumbar spine may also allow some individuals to touch the ground with their palms while keeping their knees straight.

In addition to musculoskeletal symptoms, patients commonly report shortness of breath, palpitations, dizziness, and fainting or near-fainting episodes, particularly when standing for extended periods.

Fatigue is another major concern, with patients struggling to wake up in the morning, experiencing persistent exhaustion, and having difficulty with concentration, memory, and cognitive function (commonly called "brain fog").

Sensitivity to bright lights or loud sounds is also frequently noted.

These symptoms—aside from joint issues—are linked to dysautonomia, which can also contribute to amplified pain and Fibromyalgia-like symptoms.

Many Patients Recall Being Athletic In Childhood

Often excelling in dance or gymnastics due to their flexibility. They may describe themselves as "double-jointed." A family history of similar symptoms can be a key diagnostic clue in determining whether a patient has Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

Physical signs include soft, hyper-extensible (overly stretchy) skin, particularly if the skin on the non-dominant forearm stretches more than 2 cm. The skin may also feel velvety, and patients may have stretch marks (striae) on their back, thighs, breasts, or abdomen.

Additionally, there may be a history of recurrent abdominal or inguinal hernias. Some patients report childhood pelvic floor abnormalities, including rectal or uterine prolapse.

In certain cases, an arm span greater than height may be observed, though conditions like Marfan's Syndrome should be considered first when this feature is present.

The combination of the Beighton score (a scale used to assess joint hypermobility) and the EDS Diagnostic Checklist improves diagnostic accuracy. However, a detailed medical history and physical examination remain essential in identifying systemic features of EDS.

Areas Considered when Diagnosing EDS

1) A family history of the condition,

2) Recurrent musculoskeletal complications, such as limb pain lasting more than three months,

3) Widespread pain, and

4) Spontaneous joint dislocations or instability without significant trauma.

In older patients, arthritis and weight gain due to exercise intolerance may limit mobility, making the patient’s history even more crucial for diagnosis.

Many rheumatologists refer patients for evaluation of autonomic dysfunction after excluding other connective tissue diseases. Additionally, some EDS patients are mistakenly labeled with Fibromyalgia due to symptom overlap.

Other connective tissue disorders, such as Lupus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Scleroderma, should be ruled out, as they also affect collagen and connective tissue and may cause joint hypermobility along with other potentially life-threatening complications.

Unfortunately, there is no definitive blood test, lab test, or imaging study to confirm an EDS diagnosis; it remains a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and history.

No standardized genetic test has been identified for EDS. Some patients present with this syndrome without a family history, despite a thorough search by their physician. These cases are rare, and the exact percentage is unknown.

While diagnosing hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is not necessarily difficult, it requires a thorough history and physical examination. A detailed family history is also critical, sometimes necessitating the examination of family members.

Ruling out other hereditary connective tissue disorders is essential, often requiring consultation with a skilled rheumatologist and an expert in the autonomic nervous system. Genetic testing may help exclude vascular-type EDS, Marfan’s Syndrome, and other related connective tissue diseases.

Dr. Colombo's eBook

Get your free EDS eBook!

We love to share information! Enter your information below, we will get you your copy of Dr. Colombo's EDS eBook completely free.

about the author

Dr. Joseph Colombo

Background

Dr. Colombo is trained in neurology with a background in electrical and mechanical engineering. His focus is Neuro-Cardiology. His doctorate from University of Rochester Medical School, NY, is in Neuroscience and Biomedical Engineering.

For over 25 years, Dr. Colombo has developed P&S nervous system technologies and has researched and published clinical applications and outcome studies in uses of non-invasive P&S monitoring in critical care (trauma and sepsis), anesthesiology, cardiology, endocrinology, family medicine, internal medicine, pain management, neurology, neonatology, pediatrics, psychiatry, pulmonology, sleep medicine, and more as positive, patient outcomes data are available.

He has (co-)authored over 100 journal articles internationally, and has ghost-written over 100 more. He has also (co-)authored book chapters and medical textbooks on clinical applications of, and outcomes from, non-invasive P&S guided therapy.

Dr. Colombo continues to participate in more than 50 clinical research projects world-wide and consults with physicians, clinically, on a global scale.

He has a wife of almost 40 years and two married children, and a grandchild, with over 30 years of mentoring hundreds of youths and students, including medical students.

Types of EDS

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) refers to a group of connective tissue disorders caused by genetic defects affecting collagen production. Here is a list of the different types of EDS and how they are characterized:

Hypermobile EDS

Characterized primarily by joint hypermobility affecting both large and small joints, which may lead to recurrent joint dislocations and partial dislocations.

Classical EDS

Associated with extremely stretchy, smooth skin that is fragile and bruises easily; wide, atrophic (flat or depressed) scars; and joint hypermobility. Molluscoid pseudotumors, calcified hematomas over pressure points such as the elbow, and spheroids, fat-containing cysts on forearms and shins, are also frequently seen. Hypotonia and delayed motor development may occur.

Dermatosparaxis EDS

Associated with extremely fragile skin leading to severe bruising and scarring; saggy, redundant skin, especially on the face; and hernias

Vascular EDS

Characterized by thin, translucent skin that is extremely fragile and bruises easily. Arteries and certain organs such as the intestines and uterus are also fragile and prone to rupture. People with this type typically have short stature; thin scalp hair; and characteristic facial features including large eyes, a thin nose, and lobeless ears. Joint hypermobility is present, but generally confined to the small joints (fingers, toes). Other common features include club foot; tendon and/or muscle rupture; acrogeria, defined as premature aging of the skin of the hands and feet; early onset varicose veins; pneumothorax, collapse of a lung; recession of the gums; and a decreased amount of fat under the skin.

Kyphoscoliosis EDS

Associated with severe hypotonia, decreased muscle tone, at birth, delayed motor development, progressive scoliosis (present from birth), and scleral fragility. Affected people may also have easy bruising; fragile arteries that are prone to rupture; unusually small corneas; and osteopenia, defined as low bone density. Other common features include a "marfanoid habitus" which is characterized by long, slender fingers (medically termed: arachnodactyly); unusually long limbs; and a sunken chest (medically termed: pectus excavatum) or protruding chest (medically termed: pectus carinatum).

Brittle Cornea Syndrome BCS

Characterized by thin cornea, early onset progressive keratoglobus, a degenerative non-inflammatory disorder of the eye in which structural changes within the cornea cause it to become extremely thin and change to a more globular shape than its normal gradual curve; and blue sclerae, described as a bluish coloration of the whites of the eyes.

Arthrochalasia EDS

Characterized by severe joint hypermobility and congenital hip dislocation. Other common features include fragile, elastic skin with easy bruising; hypotonia; kyphoscoliosis (kyphosis and scoliosis); and mild osteopenia.

Classical-like EDS

(clEDS) - Characterized by skin hyperextensibility with velvety skin texture and absence of atrophic scarring, generalized joint hypermobility (GJH) with or without recurrent dislocations (most often shoulder and ankle), and easily bruised skin or spontaneous ecchymoses (discolorations of the skin resulting from bleeding underneath).

Spondylodysplastic EDS

(spEDS) - Characterized by short stature (progressive in childhood), muscle hypotonia (ranging from severe congenital, to mild later-onset), and bowing of limbs.

Musculocontractural EDS

(mcEDS) - Characterized by congenital multiple contractures, characteristically adduction-flexion contractures and/or talipes equinovarus (clubfoot), characteristic craniofacial features, which are evident at birth or in early infancy, and skin features such as skin hyperextensibility, easy bruisability, skin fragility with atrophic scars, increased palmar wrinkling.

Myopathic EDS

(mEDS) - Characterized by congenital muscle hypotonia, and/or muscle atrophy, that improves with age, Proximal joint contractures (joints of the knee, hip and elbow); and hypermobility of distal joints (joints of the ankles, wrists, feet and hands).

Periodontal EDS

(pEDS) - Characterized by severe and intractable periodontitis of early onset (childhood or adolescence), lack of attached gingiva, pretibial plaques; and family history of a first-degree relative who meets clinical criteria.

Cardiac-Valvular EDS

(cvEDS) - Characterized by severe progressive cardiac-valvular problems (aortic valve, mitral valve), skin problems (hyperextensibility, atrophic scars, thin skin, easy bruising) and joint hypermobility (generalized or restricted to small joints).

Be a part of this life-changing mission!

Get In Touch

Assistance Hours

Monday – Friday 9:00am – 5:00pm

Saturday & Sunday – CLOSED

Email:

Phone Number:

(445) 455-4600